A while back I wrote about some simple tools to detect bullshit. That post was about broad cues like when numbers get too complicated, or when someone “looks the part” but isn’t saying much. Since then I picked up Calling Bullshit by Carl Bergstrom and Jevin West, a book that digs deeper into how data and statistics are often twisted to tell the wrong story.

Think of this as part two. If the first post was about sharpening your gut, this one is about sharpening your eye for how data is used. Here are a few of my favorite takeaways.

1. Average or Median?

Whenever you hear “average” be cautious. Tax cuts, for example, are often sold as saving families an average of 4000 dollars. In reality, the middle income family might get nothing while a tiny group at the top saves hundreds of thousands. The median is almost always the better metric because it tells you what the typical person experiences.

Whenever you see “average” ask yourself if median would tell a different story.

2. Percentages Gone Wrong

Percentages sound precise but they can be quietly rigged by the choice of denominator. A Wisconsin governor once claimed 50 percent job growth in his state. The trick was that most states were actually losing jobs. By mixing shrinking and growing states into the denominator, the percentage was inflated beyond recognition.

Percentages can lie if the baseline is stacked. Always check what the denominator really is.

3. Correlation vs Causation

This one never gets old. Housing prices were once found to move in step with fertility rates. Does that mean people have fewer kids because homes get expensive, or because when fewer kids are born demand for houses drops? Or is it just a fluke that disappears on the next test? Many correlations are just stories waiting to be told.

A neat chart does not prove a cause. Always ask if the relationship makes sense and if it holds up over time.

4. When Measures Become Targets

Goodhart’s Law says that once a measure becomes a target it ceases to be a good measure. Schools that teach to the test, raise scores without raising learning. Researchers who chase citations, inflate numbers without adding knowledge. Once you put a number on a pedestal, people will game it.

Don’t just look at what is being measured. Ask how people’s behavior might change once they know they are being measured.

5. Selection Bias and Experienced Averages

Insurance ads promise that people who switch, save a certain amount. Of course they do, because only people who could save, bother to switch. That’s selection bias.

Another clever twist is the gap between announced averages and experienced ones. A school may say its average class size is 50 but if a few giant classes exist, the experienced student average might be 140. That is the number that actually matters to the people inside the system.

Always check if the data includes the people who could not or did not switch and whether the average is the one actually experienced.

6. Strategies to Refute BS

The book ends with something I found quite interesting. Spotting is good, but refuting is better.

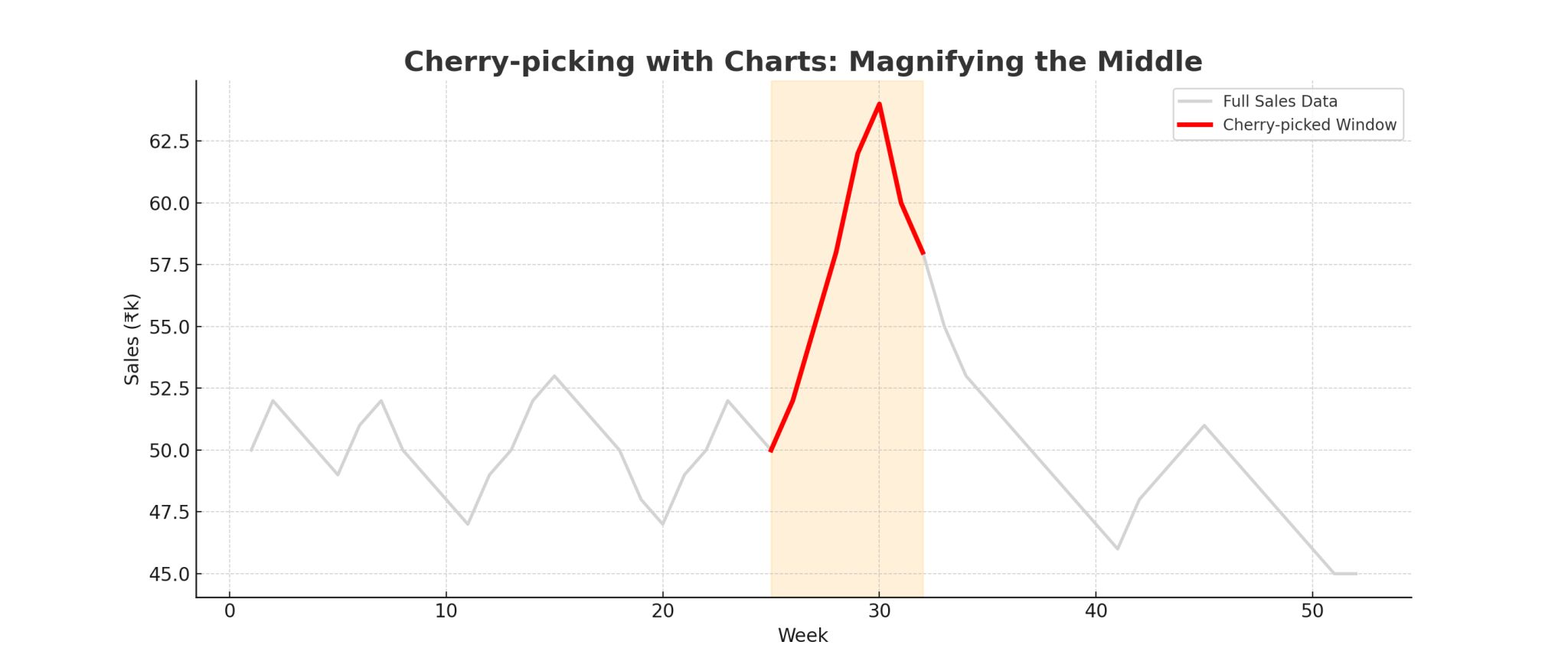

- Redraw charts to reveal what’s hidden - e.g. replot tax cuts using median instead of average to show who actually benefits

- Offer a counter example to break a claim - if someone says ‘screen time always harms kids’ point to cases where online learning helped them thrive

- Use analogies to show why a claim does not hold up - compare a ‘new batter not improving team average’ to a ‘new highway not improving commute time’

- Keep arguments simple, especially when identity is tied to belief - instead of jargon, explain in plain language why a claim is shaky

- Fill the knowledge gap, otherwise the old myth comes back - if you debunk a false cure, explain what treatments actually work

The biggest lesson from both posts is that bullshit thrives in complexity. The more tangled the numbers, the easier it is to mislead but with a few simple checks, you can cut through the fog. As Bergstrom and West remind us, calling bullshit is not a party trick, it is a moral imperative. Start with yourself, question your own blind spots and then help others see more clearly.

I run a startup called Harmonize. We are hiring and if you’re looking for an exciting startup journey, please write to jobs@harmonizehq.com. Apart from this blog, I tweet about startup life and practical wisdom in books.